Gaze

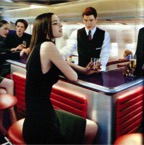

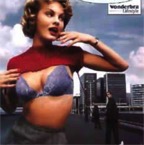

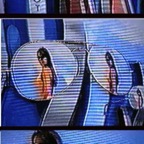

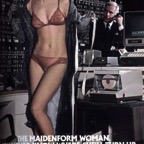

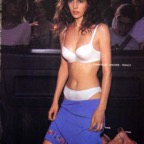

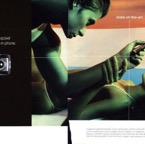

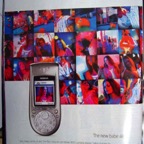

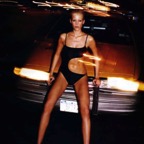

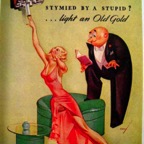

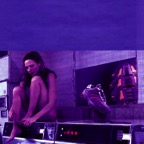

ways. The power of men over women is exhibited in many linguistic senses—more derogatory terms for women exist as compared to men; men whistle and cat-call, while there is no comparable register for women; and men have more linguistic power, because of social status, which allows them to harass women. Sexual harassment can also be understood at a visual level. Think back to the Enron scandal—not only did Enron executives commit some of the most horrific acts of elite deviance, but its executives were known to use a “hottie” board to degrade female Enron workers. Pictures of the women would be placed on a board which was used by the men to rate the “hottest” Enron workers. Visual harassment means that men have the power of the gaze—they can watch women in private (voyeurism) and in public. In the case of Enron Playboy later did a feature on “The Women of Enron.” A number of the ads in this set, as well as in the Male as Hero collection, are taken from Bordo’s “Can a Woman Harass a Man?” (1997c). Bordo’s article nicely situates the complex levels of power and interpretation involved in understanding sexual harassment. She points to the film Disclosure—in which Demi Moore “harasses” Michael Douglas, her office subordinate—as an example of the loosening of sexual harassment in popular culture. Disclosure is a pathetic film, but sadder is the idea that women are equally harassing men in the United States. Of course, any cultural analysis must take into account the intersecting levels of power (Crenshaw 1993) in society. Clearly, a woman can have more power over a man in certain situations, but the real issue is the prevalence of male power in this society, not a few cases of the contrary. What films like Disclosure or works like Mamet’s Oleanna inaccurately portray is the idea that the male harassment of females has declined or that females are equally harassing men in society. The relevance of visual harassment in understanding the male gaze cannot be overstated. A classic look at the nature of the male gaze is Walters (1995), specifically “Visual Pleasures: On Gender and Looking,” pp. 50-66. In this chapter Walters draws on the work of Berger (1985) and Mulvey (1975) and suggests a tripartite construction of the male gaze. In the case of a film, the characters in the film constitute one level, the viewers of the film another, and the director a third. The Ads: The ads below constitute all of the levels of the male gaze that I have described. I would choose ads 13 and 22 as the epitomes of the male gaze, especially as the image of the woman (image 22), taken by the man, is projected on multiple screens; and in ad 13 in which men watch the woman while the woman enjoys it. You might also note that the scenario of the woman gazing at herself is an increasingly common one (see ads 52, 55, 58). Image 31 seems to critique the male gaze, while image 21 (a television commercial) uses the male gaze in the context of blindness. Discussion Questions: (1) Why is the male gaze a pervasive form of vision in popular culture? (2) Besides advertising, can you locate other examples of the male gaze? In what media did you discover the gaze? How or why was it used? (3) Are there examples of males in advertising who are similarly objects of the gaze?